In spring 2021, Briese Schiffahrt ordered 12 new capacity optimized and eco-efficient container feeder vessels. Designed and currently under construction at the world’s leading container feeder shipyards in China, the Wengchong II 1900 and Huanghai II 1800 models enter service throughout 2023. The new ECO Container Feeders will be the first choice in the charter market in the years ahead.

A containership’s capacity is measured in TEUs. A Twenty-Foot Equivalent Unit (TEU) is a standard marine shipping container that measures 20 feet long. A 40-foot container is measured as “2 TEU”.

Container ships are distinguished into major size categories: small feeder, feeder, feedermax, Panamax, Panamax and ultra-large. Container ships under 3,000 TEU are generally called feeders.

Container Liners

Container Feeders

Feeders collect shipping containers from different ports and transport them to central container terminals where they are loaded to bigger vessels, or for further transport into the hub port’s hinterland. In that way the smaller vessels feed the larger liners, which carry thousands of containers. Over the years, feeder lines have been established by organizations transporting containers over a predefined route on a regular basis. Seaborne transport is moving towards more standardised packaging (containerisation).

The key competitive advantages of Briese Schiffahrt’s new eco container feeders is their optimized storage capacity of +10% or over 200 containers that can be loaded. The ships are highly fuel-efficient which means up top ~40% less fuel consumption which in return can prevent over 12’000 metric tons of C02 emissions annually. The vessels are dual-fuel convertible (Methanol). Their class certification “Clean Ship” and “Green Passport” ensures future-proof and sustainable operation and recycling at the end of their life.

Comparison of the new Eco Container Feeders Wengchong II 1900 and Huanghai SDARI 1800 vs. their preceding models:

| Topic | Wengchong II 1900 | Huanghai SDARI 1800 | Wengchong I 1700 | Kouan 1800 | Max. Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Built | 2023 | 2023 | 2013 | 2009 | |

| Main Engine Type | MAN B&W 6S60ME-C10.5 | MAN 6S60ME-C10.5 | MAN B&W 7S60MC-C | MAN B&W 7S60MC-C | |

| DWT t | 24’000 | 24’000 | 23’523 | 25’775 | |

| Nom. TEU (Container 20') | 1’930 | 1’781 | 1’728 | 1’794 | +8% |

| Fuel Consumption @17 KN | 25.81 | 26 | 33.5 | 41 | -37% |

| Fuel Consumption @15 KN | 17.8 | 18.4 | 24.5 | 31 | -43% |

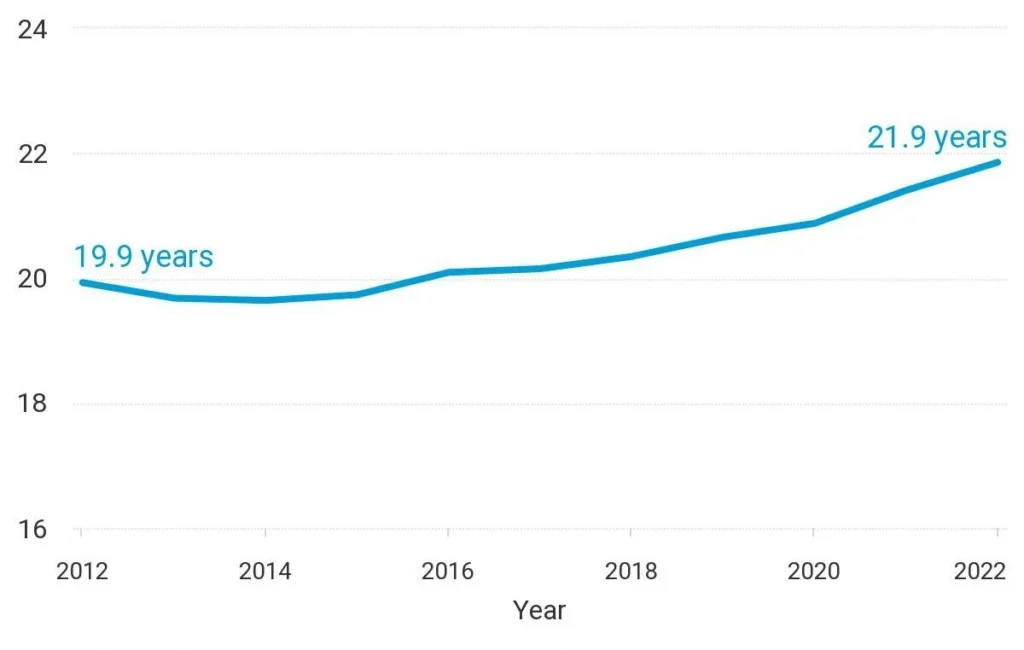

As per UNCTAD the commercial fleet’s average age is rising which is also a concern for the environment since older ships pollute more. By number of ships, the current average age is 21.9 years, and by carrying capacity 11.5 years. The average age of the world container ship fleet has increased from 10.3 to 13.7 years.

Source: UNCTAD, calculations, based on data from Clarksons Research

Note: Propelled seagoing vessels of 100 gross tons and above, as of 1 Jnauary 2022

Between the global financial crisis and Covid-19 the glopbal shipping industry was distressed and hardly and ships were built which resulted in an aging fleet. Post-pandemic the fleet is getting older partly due to shipowners’ uncertainty about future technological developments and the most cost-efficient fuels, as well as about changing regulations and carbon prices.

The world needs a new generation of ships that can use the most cost-efficient fuels and integrate seamlessly with smart digital systems. But shipbuilding volumes remain low. The global commercial fleet grew by less than 3% in 2021 – the second lowest rate since 2005.

As per BIMCO’s Container Shipping Market Overview & Outlook Q1/2023 the container fleet was growing by 4.0% in 2022 and is forecast to grow by 6.3% in 2023 and by 8.1% in 2024. While 65% of fleet growth will be concentrated in the segment of ships larger than 15,000 TEU, the fleet of container ships smaller than 3,000 TEU will reduce.

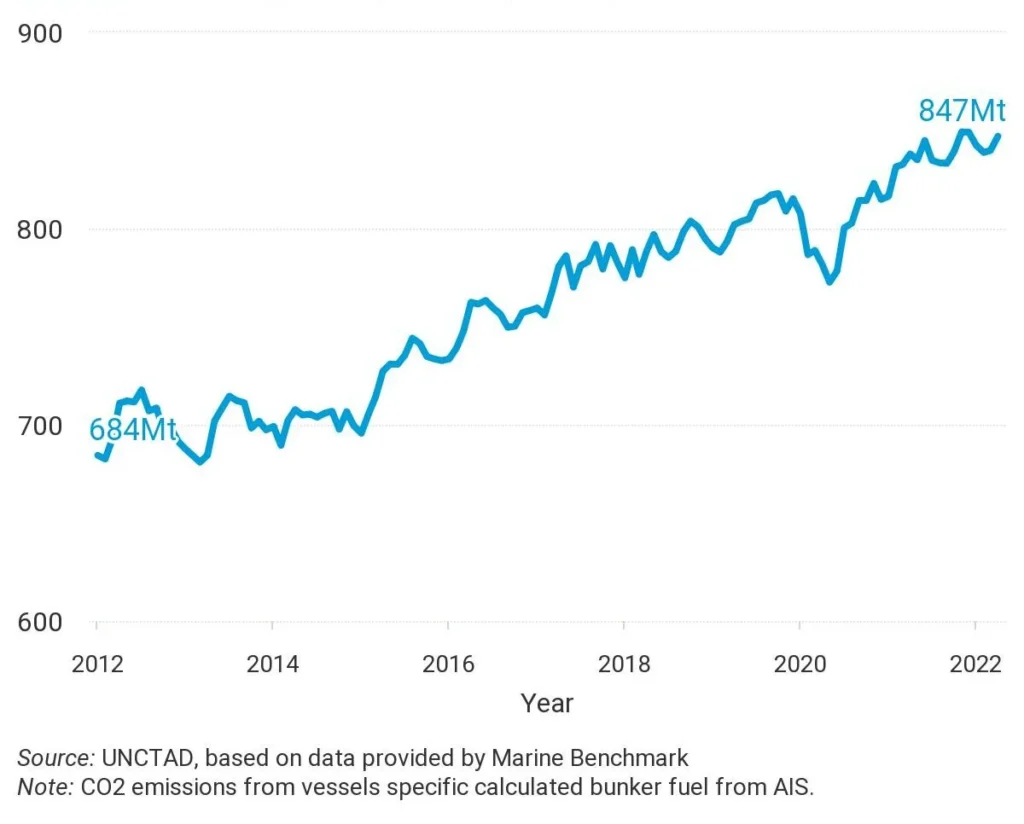

Greenhouse gas emissions from the world’s maritime fleet are heading in the wrong direction.

With design requirement for existing ships (EEXI), many vessels go for engine power limitation aka “slow steaming”. Maximum and operating speed are expected to be reduced over the next two years by 10% which will impact the overall transport capacity.

CII regulation will start to reduce sailing speed from 2024 and the impact may become significant in scrap activities from 2025 onward with favorable age profile.

The European Emission Trading System (EU ETS) will also include shipping from 2024. Starting with a phased approach the EU ETS will apply to 100% of emissions on voyages between European ports and 50% of emissions on inbound and outbound voyages. Shipping companies that do not comply with the ETS will be fined €100 for each ton of emitted CO2 as penalty.

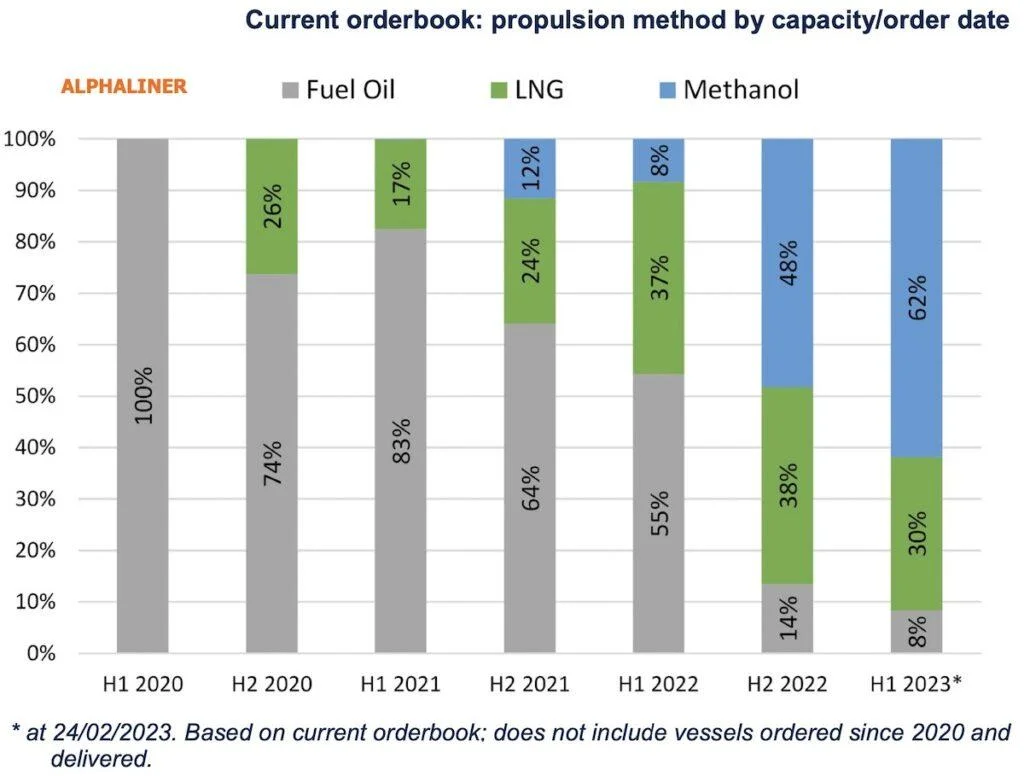

Despite the rapid acceleration in alternative fuel orders, green tonnage still represents just a fraction of the existing fleet. To date, LNG dual fuel ships represent ~2% in the fleet in the water, while the first methanol duel-fuel unitis due for delivery this year. The remainder of the existing fleet (~98%) is still powered by conventional fuel oil.

LNG dual-fuel units reached 30% of the orderbook this year. The rapid growth of methanol vessels has driven the greatest increase in green orders: methanol dual-fuel ships represent 12% of the orderbook by capacity, versus less than 1% a year ago.

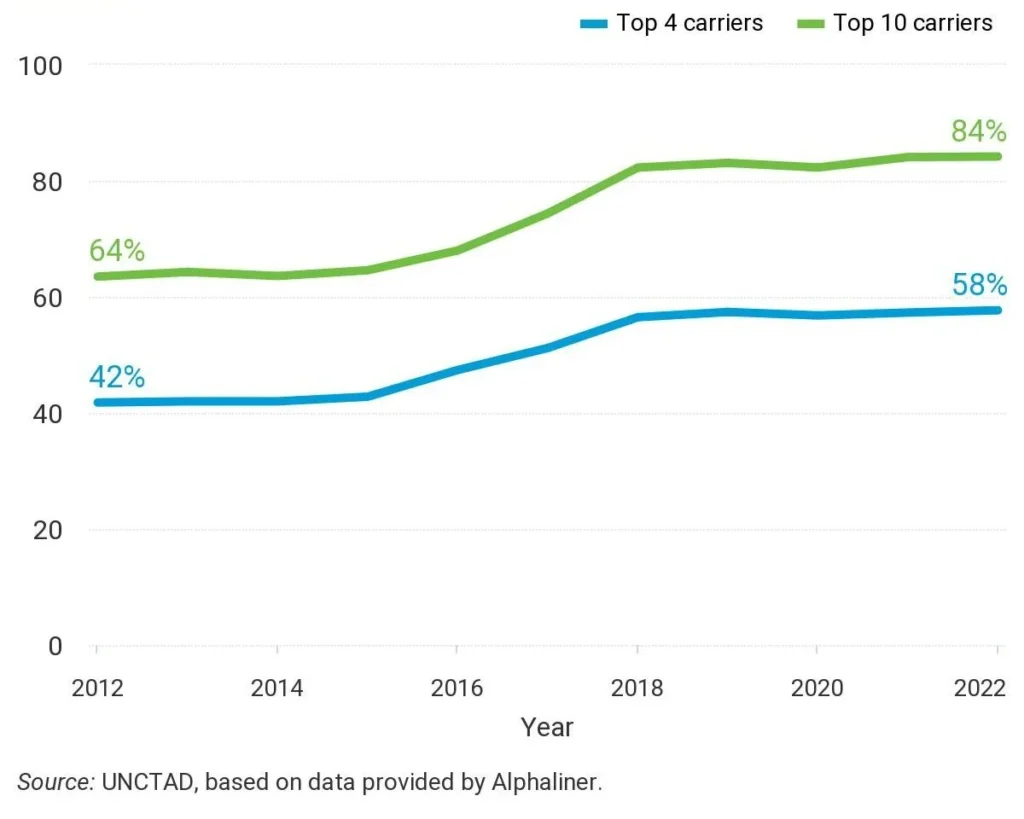

Over the last 25 years, the top 20 carriers have almost doubled their market share from 48% to 91%. And the four largest carriers now control more than half of the global container shipping capacity. Consolidation in the shipping market reduces competition and constrains supply which can result in an increase of shipping costs for businesses and thus higher prices for consumers.

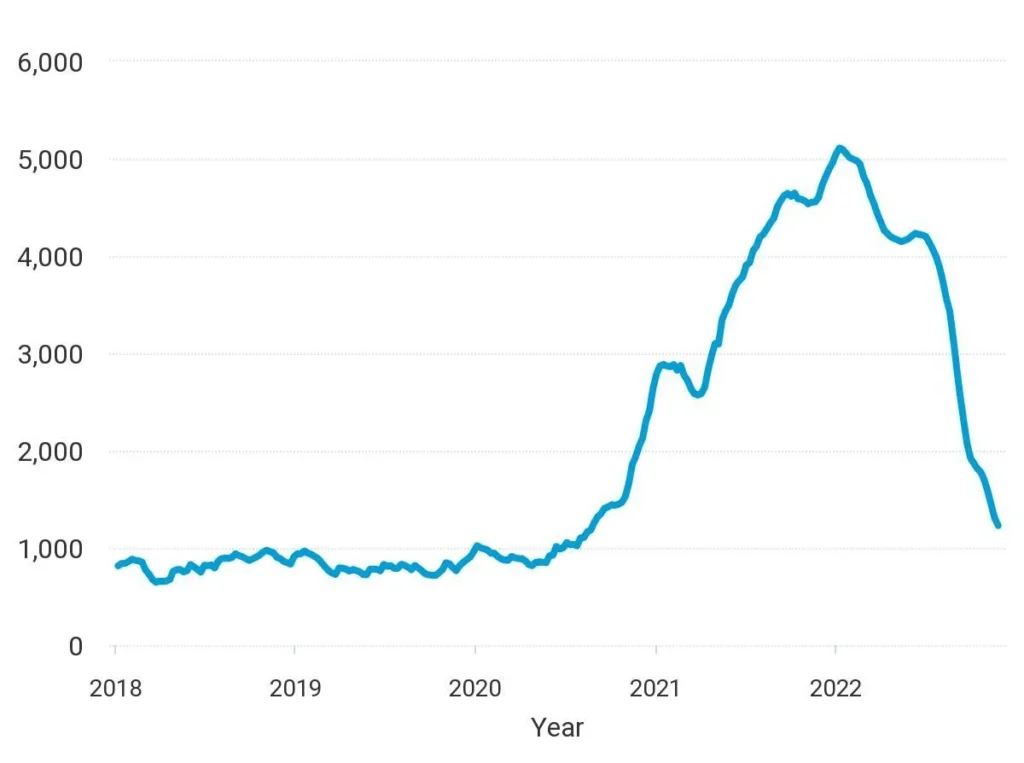

The surge in consumer spending-especially on goods ordered online-combined with supply chain disruptions and logistics constraints drove container freight rates to five times pre-pandemic levels in 2021. The spike in container shipping costs, which peaked in early 2022, led to a sharp increase in consumer prices for many goods. Although freight and charter rates have fallen since mid-2022, they are consolidating above pre-COVID-19 levels.

Source: UNCTAD, based on data from Clarksons Shipping Intelligence Network

In an increasingly unpredictable operating environment, future shipping costs will likely be higher and more volatile than in the past.

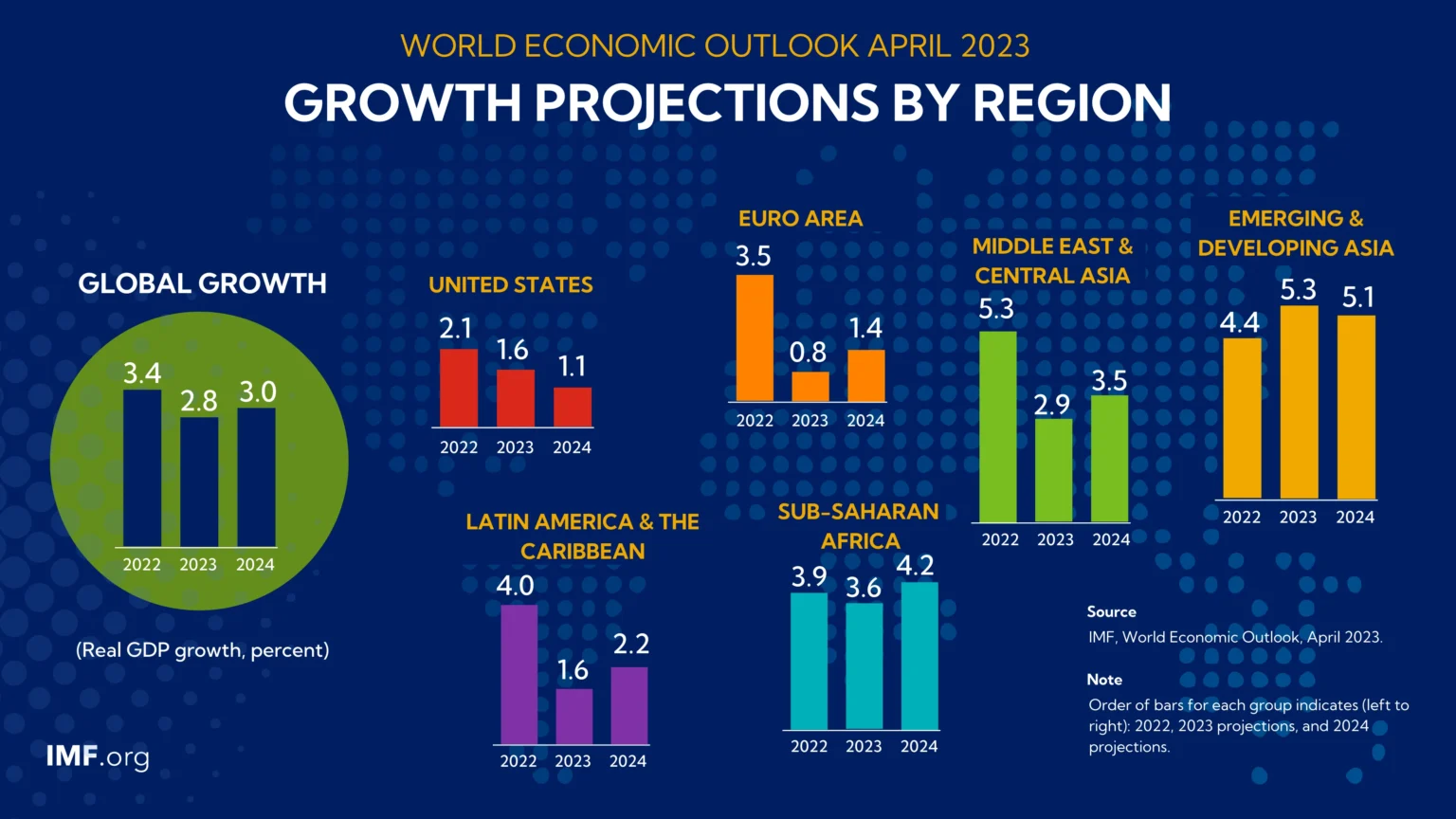

In April 2023 the IMF has revised its growth forecast for the global economy to 2.9% in 2023 and 3.1% in 2024. UNCTAD projects global maritime trade will grow 2.1% annually for the period 2023–2027. The key driver of the improvement in 2023 is an improved outlook for the Chinese economy following the relaxation of COVID-19 restrictions. This has led the IMF to increase estimated growth in 2023 to 5.2% (up from 4.4%), while the estimate for 2024 has been maintained at 4.5%.

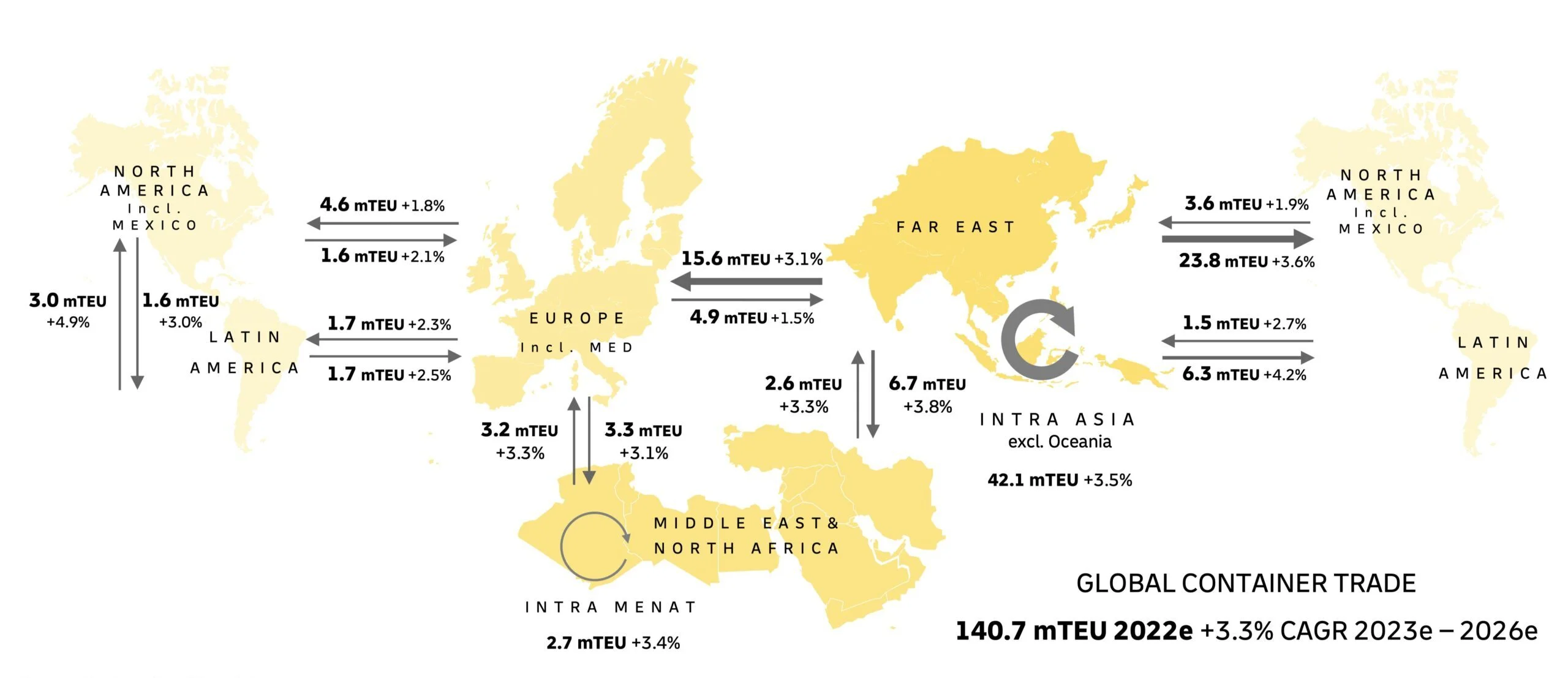

While in 2022 almost 141 million TEUs were transported, Seabury forecasts global container trade to grow by 3.3% p.a. from 2023 to 2026. An importan role plays Intra-Asia which already today is responsible for 30% of total container transportation. Asia is involved in over 75% of all container transportation globally.

Source: Seabury December22 update

© Briese Schiffahrt (Schweiz) AG, Zurich. All Rights Reserved.

BRIESE SCHIFFAHRT (SCHWEIZ) AG

St. Annagasse 18

CH-8001 Zürich

+41 44 503 54 40

info@briese.ch

www.briese.ch